New shorebird habitat created at Montezuma populated by

New shorebird habitat created at Montezuma populated bywaterfowl, shorebirds, gulls and terns. I'd make this a quiz

but I don't even know everything that's in this image!

Twenty minutes is short-changing what it deserves but you take what you can get, and I took it all. Immediately after turning into the refuge I scored a trifecta of swallows. I often see that word used as a high-falootin' way to say "three," but this was more than that. My thoughts on the drive up, when they wandered from possible shorebirds, returned to the fact I haven't seen a Bank Swallow this year.

I expected to find Tree Swallows, thought I'd pick up a few (or more) Northern Rough-winged Swallows, and I hoped for a Bank. The first birds I found were swallows, dozens of them, swarming over a vegetation-covered mudflat. Tree Swallows were easy to pick out, even before getting out of the car. Once I opened the door Northern Rough-wings were clearly audible, and I eventually scoped a single Bank Swallow on a snag among more rough-wings. One, two, three, in that order; a trifecta. Wish I'd put some money down.

Shorebird numbers and diversity weren't phenomenal but not disappointing. Least, Semipalmated, Pectoral, Solitary, both Greater and Lesser Yellowlegs, and Killdeer pocked the mudflat. Caspian Terns and Ring-billed Gulls mixed in among the Canada Geese and a few other species of waterfowl, including Blue- and Green-winged Teal, Northern Shoveler and the resident Mallards and American Black Ducks.

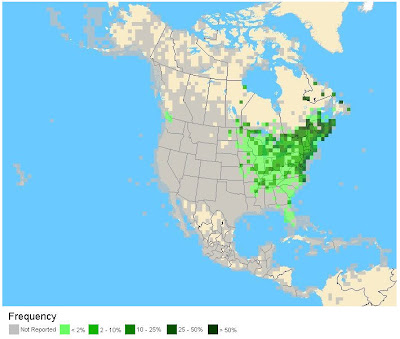

There were two highlights on this trip, the first being five Hudsonian Godwits that stuck around almost long enough for a clear photo. Hudsonian Godwits are essentially unheard of in the spring and possible in the fall, but you never plan on finding one in our region. Better and more active birders than me have chased and missed them on many occasions. This was a pretty awesome highlight! I was setting the camera when I heard them take flight so I quickly pointed-and-shot, I'm ecstatic they're even in the frame!

| From Birds |

Hudsonian Godwits flying south, identified by the

dark underwing coverts and white stripe on the upperwing.

I also heard them calling until they were out of earshot.

dark underwing coverts and white stripe on the upperwing.

I also heard them calling until they were out of earshot.

Fair warning: that's the end of the birds for this post, but you're welcome to read on to discover the other highlight as I mount my soapbox.

I must confess, each election cycle I become more of a political junkie and this week I've been hitting the stuff more than ever. Not only have I watched more speeches from the Democratic National Convention than I intended to, I've also followed some blog discussions and even watched some of the pundits blab on. Normally I can't stand the partisan punditry and spin, and that's just the talking heads -- forget about campaign mouthpieces. And this year with the Hillary-Barack drama, forget about it. But I'm tolerating it this time around as it's been a momentous week for our country.

The fact the Democrats nominated someone who looks different than those guys on our dollar bills (to paraphrase Sen. Obama) is a monumental occasion. The fact they came within a pantsuit of nominating someone of a different gender from the dollar bill guys doesn't just double the magnitude, it amplifies it immeasurably. I found myself pretty emotional listening to many of the speeches and watching the interviews with the delegates, both Obama's and Sen. Clinton's ardant supporters, participants from the Civil Rights Movement, and the everyday folks who have been affected, directly or indirectly, by the long struggle for voting rights.

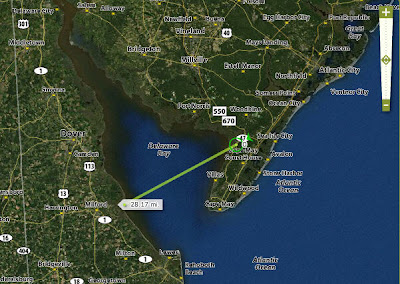

I often drive through Seneca Falls, NY after visiting Montezuma, but this time it was with a feeling of excitement and reverence as I passed by the Women's Rights National Historic Park, the first time I've felt that way as I drove through town. The significance of this site, not just for women's suffrage but for everyone, was more omnipresent today than ever before, especially this month (88th anniversary of the 19th Amendment), especially today (45 anniversary of Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech), especially right now after listening to Sen. Obama's acceptance speech. We, as a country, have come a long way, baby!

Updated to add: Boy, and now with Alaska Governor Sarah Palin on the Republican ticket, what an election this is! I can't begin to imagine what else will happen in the next 67 days.

Soapbox dismounted.

-