The World Series of Birding (WSB) is more than a birding competition. Well, at its basest level it is merely a contest to see which team can observe the most bird species in a single day within the state of New Jersey.

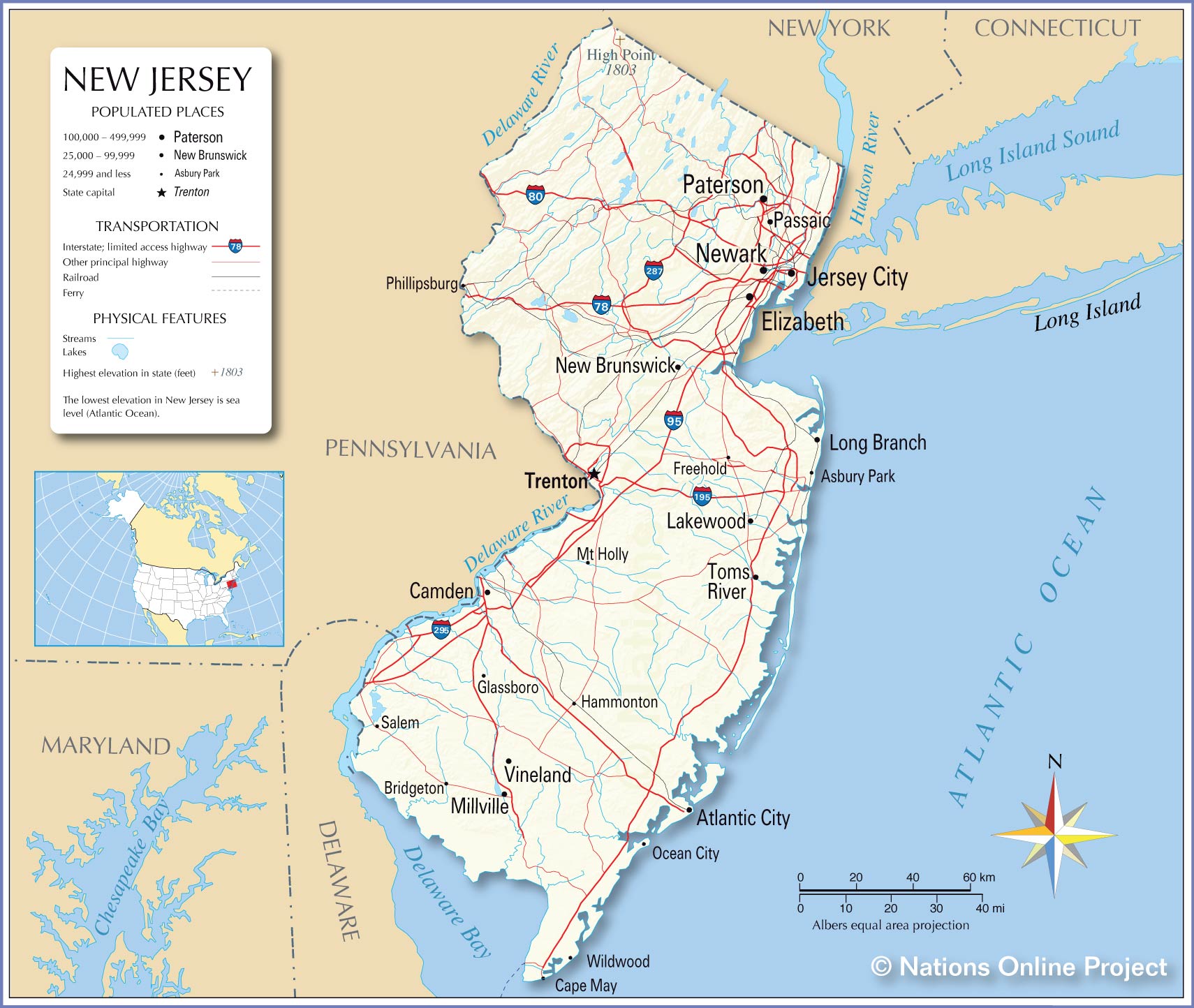

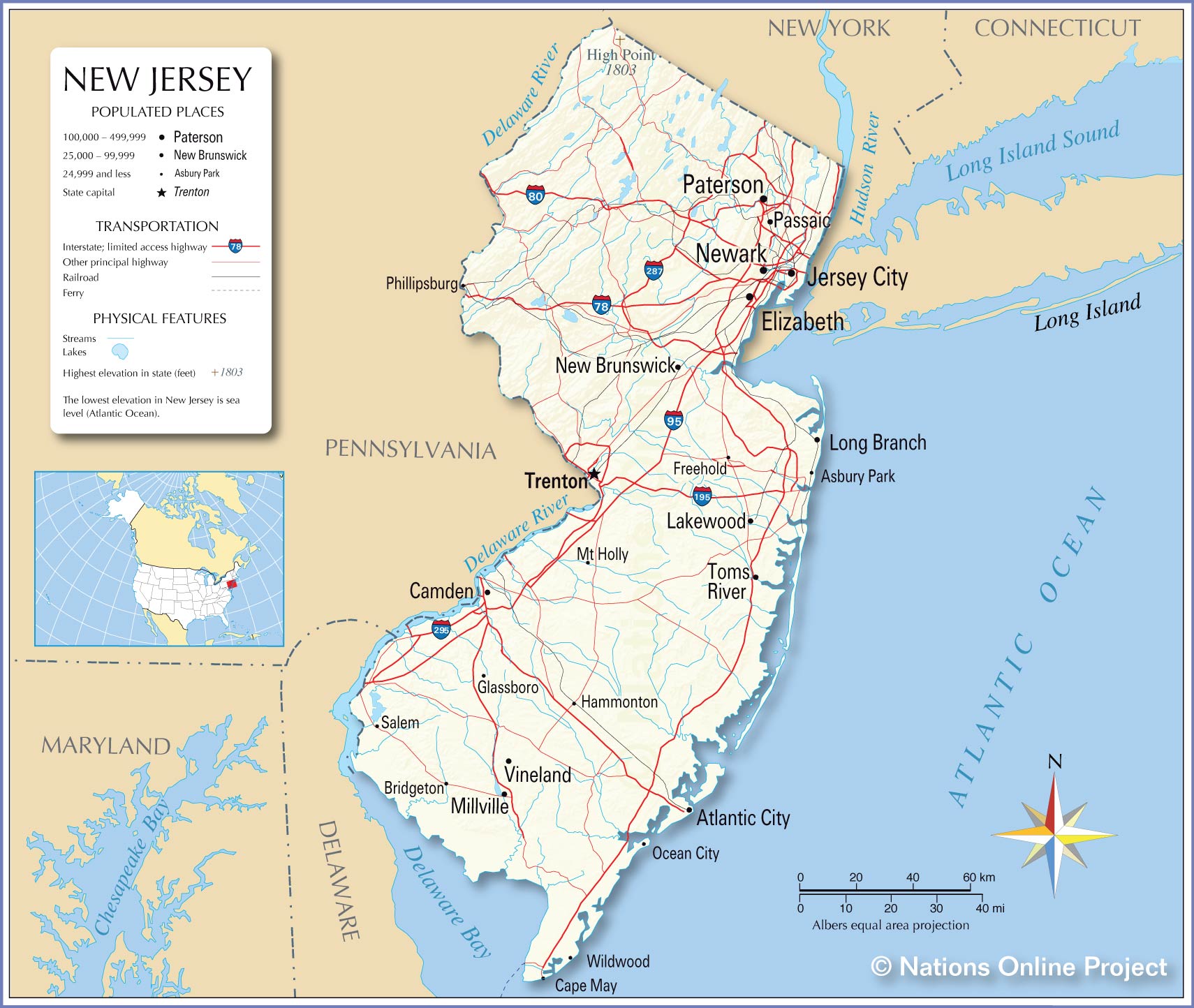

It's a small state, but I wouldn't want to paint it. Birding it is fine. Map courtesy of Nations Online Project.

It's a small state, but I wouldn't want to paint it. Birding it is fine. Map courtesy of Nations Online Project.Dig deeper and it's a pretty daunting undertaking requiring stamina, knowledge, and more than a little strategery. Developing a strategy that allows you to find 220-plus species is mind bending, a task that employs all the little grey cells you possess. Managing your time diligently requires discipline envied by the most pious of Buddhist monks (if Buddhist monks were given to envy). The extended sleep deprivation and malnutrition would make David Blaine weep. And the skills to identify all of those birds, some by sounds less than a half-second long or by a profile on the edge of visibility, takes the eidetic memory of a Good Will Hunting. And in spite of, or because of, those factors, it really is fun.

I guess -- I didn't actually compete. When you work at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, a place with dozens of world-class birders, you can bet only the best of the best are invited to join

the Sapsuckers. But I can tell you this: it's flattering to be asked to give up a few days of computer work to travel to the wilds of Jersey to help the team scout.

I'm not being facetious when I say "the wilds." Northwestern New Jersey

I'm not being facetious when I say "the wilds." Northwestern New Jersey

contradicts the strip-mall-covered and urbanized stereotypes from movies.Scouting is an essential part of the competition. It turns out you can't just show up and expect to make a 200 species-plus run through the state. I mean, you can have that expectation, but it's a bit naive. You'd be fooling yourself. There is a lot of preparation involved in tracking every bird in the state and determining how to visit them all, or at least one of each species. It means studying New Jersey, committing to memory the variety of habitats throughout the state, then coupling that knowledge with a thorough understanding of which birds use those habitats. Then, couple that with the phenology of bird movements -- when are those birds are actually in Jersey? When do the snowbirds head north, when do the neotrops return? Oh, and remember, you only have a single 24-hour period, so you need to know the best time of day to find them.

Many Black-throated Blue Warblers pass through the state, but some breed.

Many Black-throated Blue Warblers pass through the state, but some breed.

You have to know where if you want to be sure to add them to your list.

That's why you scout. The mission, which I chose to accept: descend on New Jersey and stake out as many birds as you can.

So, what do you stake out? Ideally, everything. Some birds you simply shouldn't worry about. American Robin, drive by any lawn and there you go! American Crow? C'mon. They're everywhere. Northern Cardinal? Please, missing these guys is impossible, right?

Finding a Blue-headed Vireo nest may be the difference between

Finding a Blue-headed Vireo nest may be the difference between

adding this species for the day or missing it altogether.But there's a lesson many teams have learned over the years: take nothing for granted. What if it's pouring rain and no bird is calling? How do you efficiently find birds that were singing loudly a day or two before, but are hunkered down and silent? You don't have time to traipse through the woods looking for them, hoping to cross paths. You need to know precisely where to look. And even if it is amiable weather, you need to know what time to be at each location. Birds aren't signing all day; when does each species start? When do they quiet down? What locations are active early, which ones come alive late? It pays to know when the birds are most active, singing and calling without restraint.

Canada Warblers often return to New Jersey shortly before the Big Day.

Canada Warblers often return to New Jersey shortly before the Big Day.

Visiting their territories lets you know exactly when they return.I had some specific tasks, I had some general assignments. The weather was a mixed bag. I listened for saw-whet owls in the pouring rain, I watched migrant warblers in a sunny park. I spent hours by myself, not coming in contact with another person. I fought traffic on the Jersey Turnpike and sought much-needed birds in the middle of Newark. I had some successes and some complete failures. All of that information, merged with reports from other scouts, was fed to the Sapsuckers who incorporated it into their Big Day strategy.

More on the day-to-day activities of a scout to come, but how did it all work out for the Sapsuckers? The "tweet" came in on Sunday morning at 12:07 AM (you know I was still up, anxiously awaiting the results): their final tally was 221 species. I'd have to wait until late Sunday morning to hear how that stacked up against the other teams. Pretty well, it turned out, but not well enough to win.

More to come . . . .

-