From the photo files from 17 May 2009 . . .

Our daughter, Reina, is five, and if you ask her career aspirations and goals she'll tell you she's strongly drawn towards education and the service industry.

Not in those words, of course, she just blurts out, "I wanna be a teacher and a waitress." And yes, we know she'll need that second income if she's gonna be a teacher.

But that all changed on a cool and sunny morning this past May. We were headed for an overnight to Rochester, NY, partly to visit my folks, partly to visit the

Braddock Bay Bird Observatory's Kaiser-Manitou Beach Banding Station. I've been anxious to introduce Reina to bird banding, to the idea of handling wild birds to learn about them. This spring seemed perfect. She's not old enough to process the birds, of course, but she is old enough to appreciate what was going on and why. And not yet old enough to be jaded and cynical about the experience.

We planned to meet Laura Kammermeier, friend,

fellow blogger, and former colleague who conveniently now lives near my folks, at the observatory's headquarters along the shore of Lake Ontario (Laura recounted her take of that morning's events, along with fantastic photos, in

Bird Banding @ Braddock Bay Bird Observatory.

We walked in the door of the small, rustic facility and found a dozen animated folks busily interacting around a tall table. It was like walking into a local bar, where everyone pauses, glances over at the newcomers to give the ol' once over, then went back to their business. We weren't sure what to do, or what not to do, so we walked over to see what everyone was doing.

As we sidled up a woman turned to Reina, who was sporting the remnants of a butterfly face-painting from the day before, and asked, "Have you ever heard a hummingbird's heart?" To my surprise and complete joy Reina did not grab my leg and hide behind me.

"Nooo . . ." she sounded intrigued but unsure of the whole idea. She knows humans have hearts from playing with the models in the anatomy lab at my wife's college, but I'm not sure she transposed that information to other animals.

The woman crouched next to Reina held a

Ruby-throated Hummingbird to her ear. As much as

I wanted to hear the beating heart I stayed back and took pictures of a watershed moment. Her expression is all you need to realize something pivotal just happened in her life.

"I can hear its heart beating?

"I can hear its heart beating?

I can hear its heart beating!"

Reina watched her finish processing the bird, then got an offer I was hoping would come. "Would you like to release the hummingbird?" Again the expression of uncertainty, so I explained.

"They got all the information they need from measuring the bird in here, now they let it go back into the wild. Let's go outside, and you'll get to hold the hummingbird until he decides to leave. You know, if you want to. Otherwise I'll do it." I was only half-goading her, I really wanted to release a bird!

"No, daddy! I can do it!" Yeah, she wanted to.

Reina held the male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, waiting for him to

Reina held the male Ruby-throated Hummingbird, waiting for him to

either realize he's free to go, or to decide he was ready to take his leave

of all of us. He stuck around for about 30 seconds before taking flight,

29 seconds longer than it took for Reina to contemplate a new career path.

Then it was back inside to watch more processing of birds. There was only one hummingbird banded while we were there, but plenty of other action. The banding crew was extremely generous about letting us watch up-close-and-personal, especially the students of the banding class that was underway. We didn't even realize, everyone was so professional!

A male Mourning Warbler: one of the most

A male Mourning Warbler: one of the most

beautiful birds we saw that morning, maybe because

they are so skulky and hard to observe in our region.

I'm always amazed how different birds look in the bander's grip compared to seeing

I'm always amazed how different birds look in the bander's grip compared to seeing

one in the wild, like this Northern Waterthrush. It appeared so different than a

Northern Waterthrush in the wild, where they're behaving waterthrushy.

Another bird of subtle beauty like the waterthrush:

Another bird of subtle beauty like the waterthrush:

the warm tones of a Swamp Sparrow. Back to the flashy colors of the warblers. This is another of my favorite images I've captured this year, a college student processing a

Magnolia Warbler. Though technically accurate, "processing" sounds too clinical here, there is much deeper going on in the relationship between researcher and specimen. (And my sincere apologies: I did not catch the student's name, though we talked quite a bit - turns out she attends my undergrad alma mater, Hobart and William Smith Colleges. This photo deserves a more personal attribute.)

Open caption: how would you describe this moment?

Open caption: how would you describe this moment? Again Reina does the honors, though the Maggie didn't stick around.

Again Reina does the honors, though the Maggie didn't stick around.

He merely bounced off of Reina's open palm, off to turn his fancy

to flights of love. Or something more avian, but along those lines. Some birds don't look like what you're used to seeing flitting about in the trees,

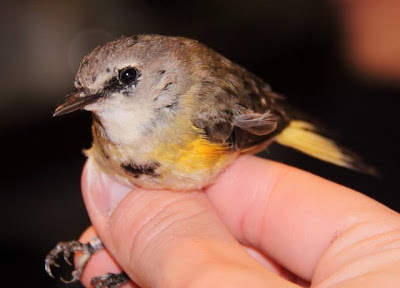

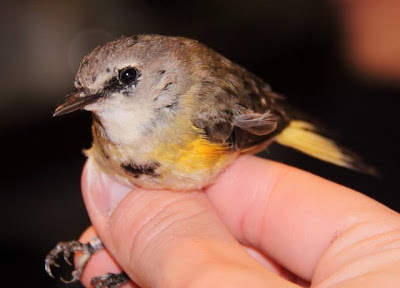

Some birds don't look like what you're used to seeing flitting about in the trees,

like this young male American Redstart. Yellow where he will eventually be

orange (like a female), but the black lores (area between the eye and the bill) and

the black feathers coming in on his breast, face and cheek confirm he's a male.

Not all the captured species have been absent from our New York backyard since last fall, plenty of year-round residents are caught in the nets. Of course, they're processed, too: collecting data on our common birds is in lockstep with the goal of keeping them common.

Blue Jays, though familiar in western New York year-

Blue Jays, though familiar in western New York year-

round, do migrate. This bird may be returning from a

mid-Atlantic state where the winters are more moderate.  Not all the captures are avian, either. Dragonflies, such as this common

Not all the captures are avian, either. Dragonflies, such as this common

Green Darner, are gently removed and released when caught.

In the 90 minutes or so we stayed we saw some two dozen birds pass through the capable hands of the BBBO staff, volunteers, and the students, each released adorned with a flashy silver band stamped with a unique identifying code by the Fish and Wildlife Service. If any of these birds are captured again they'll provide an important piece of information about that bird's travels and condition, shedding insight on the species as a whole and migration in general.

Through it all Reina helped release a few birds, as well as followed the banders as they checked the nets for newly caught birds (nets are checked every 30 minutes, at least). Actually, she only followed during the first net run. She lead the way on the subsequent trips.

Now ask her what she wants to be when she's grown and you'll hear, "I want to band birds, be a waitress, and teach." The requisite crack still applies, you're going to need the combined salaries to make ends meet. At least she'll be well rounded.

-

No idea, but these are common in our garden, you can see why.

No idea, but these are common in our garden, you can see why.

I'm frustrated I haven't figured this one out, maybe the female

I'm frustrated I haven't figured this one out, maybe the female