Dateline: Autumn 1997, El Yunque National Forest, Puerto Rico

In 1997 the mycologist (my then-girlfriend, now-wife) was working on her dissertation at the University of Arkansas. A great natural state, Arkansas, but when she was offered a chance to perform research in Puerto Rico for a semester she jumped at the chance. I also jumped and we were off for three months of working in the El Yunque National Forest (and don't tell anyone: also playing in El Yunque and the rest of the island).

I supported myself by working on two different research projects while there, and perhaps stating the obvious I was always on call to be a field assistant for the mycologist. Each project involved a fair amount of time hiking throughout the various forest types in El Yunque and I was giddy about this prospect of finding Puerto Rican Parrots. Scientifically known as Amazona vittata, they are the least-expected but most-desired birds to see on the island.

To really understand how adrenaline-surging this opportunity was you should take a few minutes to read a recent 10000Birds.com post about the history and status of the critically-endangered PR Parrot. Brief summary: population estimates from pre-Colombian times ranged between 100,000 to 1,000,000 individuals spread across Puerto Rico, Culebra, Vieques, and Mona, possibly across the northern Lesser Antilles. By the time we arrived in 1997 there were approximately 40 wild birds restricted to a single mountain range on Puerto Rico. Because my job(s), by definition, would require spending most of each day in areas favored by the parrots I would have an above-average chance to come across them in the wild. And I had three months to do so.

My quest: a pair of Puerto Rican Parrots. Actually, I was

My quest: a pair of Puerto Rican Parrots. Actually, I washoping for a flock. Breeding wouldn't occur until February,

we were leaving in December. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

For the more numerically-inclined among you, check out this recent paper if you're interested in some probability modeling. From the abstract, "We develop models to assess the probability of extinction and the search effort necessary to detect an individual in a small population." (Emphasis mine). That'll tell you exactly what my chances were.

One particularly sunny day, partway through our tenure in PR, we were hiking along a closed road in an area we hadn't visited before. To that point I hadn't seen nor heard PR Parrots. In fact, no parrots had been noted in the rainforest at all. Other parrot species, such as the introduced-and-established White-fronted Parrot (Amazona albifrons) and Red-crowned Parrot (Amazona viridigenalis), among others, prefer the lowlands along the coast. But if you saw/heard a parrot in the rainforest, I was told by other biologists, it was almost certainly a PR Parrot. Naturally, my ears remained tuned for any parrot-ish vocalizations, my eyes peeled for flying birds above the canopy. I wasn't able to convince myself that I'd find a flock foraging among the foliage, having watched Orange-winged Parrots (Amazona amizonica) completely disappear in plain sight into the trees in our yard.

One view of the El Yunque forest. There are several different

One view of the El Yunque forest. There are several differentforest types in the forest. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

I didn't know why, but as we walked the road I suddenly felt a tingling in my spine, goosebumps appeared on my arms. It slowly dawned on me: I could hear parrots. Not the classic squawking, no one begging for crackers, but something new. Something kind of like this (note: link will open/play an mp3 if you have Quicktime installed). The mycologist heard it, too. Our eyes met, she gave me a partly excited, partly resigned look that said, "Go for it." She knew I'd be useless if I didn't chase it.

I was off like a shot, bee-lining towards the sounds. Off the road, into the forest, slipping along a path, slipping off the path, crashing through undergrowth taller than me. I stopped and listened, they hadn't flown. Moving slower and more carefully I pushed on, sounds getting closer. I inched through the foliage, brushing leaves wider than me aside, and climbed a small rise. I threaded my way through a couple of plants and froze. About 30 feet in front of me was a parrot!

Classic cream-colored parrot bill, short, blunt tail characteristic of Amazona parrots, emerald-green body, wide white eye-rings, some blue evident in the folded wing - looked good! And I was up in the rainforest, away from the lowlands . . . I was staring at one of the rarest birds in world. Full of emotion, I stared. It calmly watched me, slightly moving its head, blinking. In the now-silent forest I tried to take in every detail, committing this bird to memory. It had that typical bemused parrot look, like there was something funny I wasn't quite getting. I shared a few minutes with this bird and began breathing again as the lister in me mentally ticked my life list up a notch.

I thought about this species' rough existence. Hunted as a food source by the Taínos, then the devastating loss of habitat starting post-European colonization that caused numbers to plummet. A species in peril, the dwindling population endured hurricanes, parasites, predators, and competitors. The numbers, which dropped to an all-time low of only 13 existing birds in 1975, has rebounded. In 1997, as I communed with this single bird, there were some 40 wild birds and about a hundred in captivity. The progress was heartening, but as I bonded with this individual I tried to convey that I knew the birds weren't out of the woods yet (actually, I should say they weren't into the woods yet, where they belonged). I whispered that I would do my part to help them get there.

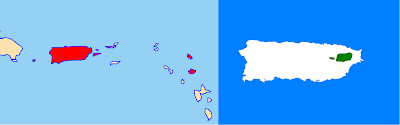

Amazona vittata range. Historical in red (left) and

Amazona vittata range. Historical in red (left) andcurrent in green (right). Image courtesy Wikipedia.

My eyes wandered, searching for the others in the flock. That's when I noticed something weird. The bird was perched, but it didn't seem to be perched on anything. I mean, you'd expect it to be gripping a limb, a broad leaf, some oversize fruit, but there wasn't a tree nearby. It just improbably hung there. It impossibly hung in mid-air, continuing to watch, perhaps smirking. "C'mon, figure this one out, you can do it."

Careful scrutiny of the situation showed it was, in fact, perched on something. It was gripping the sides of a large enclosure. Thin, black, interlaced wire was near invisible within the forest foliage and dappled sunlight, but it was there. I knew there was a captive breeding facility within the park boundaries, and I suddenly realized that I had found it. I backed away slowly, not wanting to have to explain why I was sneaking up on the backside of a federal building to the authorities. I've never heard anything about Puerto Rican jails, but I can't imagine a scenario I would want to spend time in one.

Back on the road I recounted the story to the mycologist and removed that mental "tick" from my life list. In one sense it didn't matter that I stumbled across a captive parrot rather than a wild, free-flying bird. I still shared an encounter with one of the rarest species on the planet, something I had anticipated but never really expected. A beautiful moment, one I knew I'd be flashing back to for years to come.

Epilogue

That afternoon, back in the town of Sabana, we were putting away equipment in the research facility where the mycologist was based during our stay. If some of the wind was taken from my sails when I realized I was watching a captive parrot rather than a wild one, the rest was sucked away after I recounted my episode to Esteban, the field technician I periodically worked with.

Hispaniolan Parrots, look-alikes of, and surrogate parents

Hispaniolan Parrots, look-alikes of, and surrogate parentsfor, Puerto Rican Parrots. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

"I hate to tell you this," he began. "They keep the Iguaca, the Puerto Rican Amazons, inside. The ones outdoors are Hispaniolan Parrots. You know, Amazona ventralis." He went on to say eggs laid by captive PR Parrots are moved to active nests of captive Hispaniolan Parrots, who seem to be better mothers. In the excitement and emotion of seeing this bird, and puzzling through the curious circumstance, I failed to take into account all of the field marks, never noticing that it had a prominent white forehead, not red. There's a lesson learned, hopefully I'll once again have an occasion to apply that reinforced knowledge.

This watercolor hangs in our house, given to me by

This watercolor hangs in our house, given to me bythe mycologist for my birthday that year. I like how

the red is inescapable, a constant reminder of that day.

-

5 comments:

A great read. What a twist! I really felt for you.

When you do get those PR Parrots, it'll be a great bookend.

Great story :)

There are estimates that PR Parrot occurred across the LA? I didn't know that.

Glad you guys enjoyed it, I can (almost) laugh about it now. I'm hoping to bookend this story soon!

I edited the historical distribution I noted to leave a little wiggle room because most sources I read only highlighted the PR islands. There were a couple of sources that reference additional Lesser Antilles islands but I'm not sure how established or credible that is. I should have noted that the first time around, thanks for pointing it out!

-Mike

Great story, but ouch. I hope you can bookend it too.

By the way, my 6 random things is finally up. - thanks for the task.

I found you on Facebook today in the Nature Blog category. I read this story at 10K Birds a few days ago. Nice to put the blog with the blogger. Great story and love the art.

Post a Comment