When I

last posted our hero was patrolling Plymouth Harbor on a balmy day in January. Although I was also scouring the harbor that day, the hero is the

Ivory Gull. And in one of those rare chase-moments it was the first bird my binoculars rested on, almost immediately after getting out of the car.

As I worked out a couple of muscle cramps and cracked my back a few times, all the while on the phone with Marshall Iliff, I watched a small group of gulls flying south towards a breakwater about 300 meters from where I stood. A single bird trailed a few meters behind, as if trying to keep up. The wing beats were a bit quicker, the flight more buoyant, almost tern-like. It was smaller than the others, paler than the others. This bird almost glowed, no gray or black to absorb the sunlight. A brief check with the bins and I told Marshall I had

the bird.

They landed on the railing of what appeared to be a bridge on the breakwater, not fifty feet from a coalescence of binoculars, tripods, scopes, and cameras. I thought of the listserve posts where the bird the bird flew near the observers, flew over the observers, even landing behind the observers to perch on a snowbank a few yards from their feet. It's reported that

Ivory Gulls can be quite tame and often approached by people. If that's true, that our presence wasn't stressing the bird, I was excited for an up-close-and-personal time with this rare visitor.

What's missing from this row of gulls? The target bird.

What's missing from this row of gulls? The target bird.I walked out towards the breakwater, crossed the parking lot where I should have parked, and set up my scope. I trained it on the breakwater bridge and scanned for the distinctly unmarked bird. Slowly panned along the row of gulls, right to left, waiting for the one to jump out. Didn't see it. Re-scan, slower, left to right. Still nothing.

I went back and forth across the gulls twice more with the scope, then scanned with binoculars. It wasn't there, not hidden behind a

Herring Gull, not oddly-lit so it mimicked a local resident gull with a gray back and dark wing tips. It simply wasn't there. I cheated, sneaking a peek at the other birders. Surely they'd all be gazing uniformly in one direction, the gull sitting at the intersection of their various optics.

First-cycle Herring Gull. There are other birds to

First-cycle Herring Gull. There are other birds to

watch on a chase, after all.This is a good moment to point out bird chases are not only about the bird. A secondary purpose is to socialize, meeting local birders and those from the region, even some from across the country, catching up with those you haven't seen in ages. Birders from New York, Pennsylvania, Maine, New Jersey, Virginia, Maryland, and elsewhere were meeting and greeting. I heard everything from, "Nice to be able to put a face with your name" to "It's been a while, since the Wood Sandpiper in Delaware, right?"

What I didn't hear were directions on where the bird happened to be at that particular moment. I started to wonder if the ten-second flight was going to be the extent of my Ivory Gull sighting, one of those "better than nothing, but

c'mon" sightings.

Looking out over Plymouth Harbor.

Looking out over Plymouth Harbor.

Somewhere out there is the Ivory Gull.I asked a woman who seemed to be in charge of the event -- she was the loudest, orchestrating who should put what scope where - if she'd seen the gull fly.

"It's up on the

railing, have a look, it's simply

glorious!" She turned to look, noticed it was missing. "Agnes,

where's the bird? Have

you seen it, Mildred?

Where's it off to?" It was reminiscent of Monty Python sketches

like this one; wrong accent, right pitch. I turned my attention to the handful of gulls lazily circling the harbor.

Ring-billeds,

Great Black-backs, Herring, none of the white-winged gulls, none Ivory.

How about on the water? I'd read Ivory Gulls tend not to swim as much as other gulls, but they certainly can. I scanned the water surface, flat as glass on this sunny morning. More non-target gulls, along with

Common Eider,

Red-breasted Merganser,

Bufflehead,

American Coot, and

Common Loon. I paused on each small piece of floating ice, they mimicked a white bird swimming on the water. None were the gull. One of those pieces, however, had the gull sitting on it. About 100 meters from where I stood the bird was loafing on what must have vaguely seemed like home.

The Ivory Gull, blending in: white on white.

The Ivory Gull, blending in: white on white.I called out that I refound it, several birders re-aligned their scopes and went back to more Monty Python. "

Ooooh, look at it now! So

cultured, beautiful plumage. Have you tried the clam chowder at the East Bay Grille?

Brilliant!"

For some, this is where it could become boring. The bird perched on the ice for the next hour and forty-five minutes, barely moving. No flying in to tear at a chicken carcass, no interacting with other gulls, no raucous vocalizing. No aerial acrobatics, none of the buoyant flying I noted when I arrived.

Uh-oh, is that a yawn? The action might really slow down now!

Uh-oh, is that a yawn? The action might really slow down now!But there are plenty of other aspects to focus on. I was soon joined by a birder from Maryland. He and his girlfriend left home the night before, arrived in Gloucester before daylight, and spent several hours not finding that bird (after daylight), then bailed and headed to Plymouth. Slightly out of breath, "Please tell me this one is around!"

"Right here in the scope." On par with watching a new species, taking in all of its uniqueness, is helping another "chaser" get on the bird. He took it in, satisfied he at least saw it, then went to get his scope, camera, and bins. Oh, and to wake his girlfriend.

I had plenty of time to take in the plumage, which was immaculate. Completely unblemished, snow white.

An impromptu digiscope, which came out much better than I expected.

An impromptu digiscope, which came out much better than I expected.

The legs are black, the bill dark (actually greenish) with yellow tip.

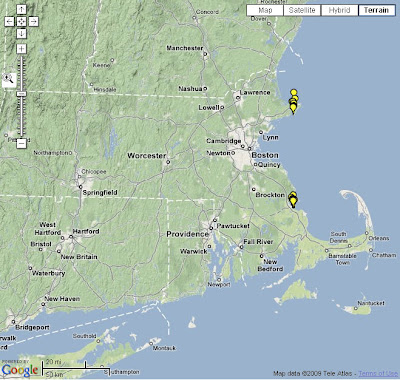

Pure, one word that comes to mind, as the driven snow. Immature birds are flecked with dark markings across the face and wings and show a dark tip to the tail feathers. All I saw was dark legs, dark, yellow-tipped bill, a dark eye, and white. The Gloucester bird showed a few dark smudges on the flanks, indicating it was a separate bird. When the two birds were reported at the same time in two different locations, that definitively showed there were two adult birds on the Massachusetts coast at the same time, something I'm not sure has ever happened. In fact, the last adult in Massachusetts was in the 1800's (the 1976 bird was an immature, three birds in the 1940's were also immatures). Adults are not completely unknown, an adult was found on the Hudson River as recent as two years ago, but they appear to be less common than vagrant immature birds.

What were two adults doing so far away from their normal wintering range? And what are the odds they'd wind up 45 miles away from each other? I have no idea, and I'm not sure anyone else does. We simply don't know a whole lot about them. The

Birds of North America Online states, "knowledge of the life history of Ivory Gulls has been slow to accrue and there have been no truly long-term studies of its demography." Is it possible they come south more than we think but go unrecorded? After all, birders can't be everywhere. But it seems if this was a regular event the odds of an experienced observer encountering one (or more) would favor more documentation.

Settling in for a nap, giving the two dozen observers lots of

Settling in for a nap, giving the two dozen observers lots of

time to contemplate all aspects of this amazing species.It does seem something is going on this year. In the east, most vagrant records come from the northeastern states, some from the mid-Atlantic, possibly a record from North Carolina. But in numbers? Nick, the Shorebirder, had already posted about

an incursion of Ivory Gulls in Newfoundland and Labrador. More recently Jochen at Belltower Birding highlighted some

interesting European sightings of Arctic gulls. An Ivory Gull in southern France? A Ross's Gull in central Spain? Jochen translates this to North American terms,

The magnitude of this incident is comparable to an Ivory Gull being found on the coasts of Georgia while an Alabama inland lake hosts a Ross's at the same time.

What's going on in the Arctic to prompt these movements? Something must be underlying these vagrant wanderings, how best to unravel this mystery?

My mind wandered back to more mundane questions. Your mind has to wander in these cases: you'd have to play the two hours I had with the gull in fast motion to make it physically interesting. The rough breakdown of Ivory Gull activity was nearly 90 minutes of near-motionless resting on the chunk of ice, another 15 minutes lethargically stretching and uninspired preening, ten minutes floating next to the ice chunk. Physically the bird was relatively passive, but that didn't slow the myriad of questions running through my head.

It then lifted off the water, circled twice to gain a little altitude, then headed farther south into the harbor. It ultimately settled near a growing colony of gulls on the water, far enough away that it became impossible to tell which gull was which. After watching what essentially amounted to specks in the distance for another few minutes, hoping for a return flight, I understood it was time to break away for my lunch meeting. The bird had left me, and it was time to leave Plymouth.

More Ivory Gull information available at:

All About BirdsBNA Online (subscription needed)

One (of many) news pieces about this gull:

Mature Arctic Ivory Gull Seen in Massachusetts (Patriot Ledger)

-