I was fighting with electronics, bungee cords, and duct tape, trying to mount a skyward-pointing microphone; Tom and Shawn were hoping for a few shorebirds pausing in their southward migration. And as I was serenaded by a cacophony of Blue Jays, American Crows, and Canada Geese, they discovered a Magnificent Frigatebird.

The first Magnificent Frigatebird observed in the Cayuga Lake Basin,

The first Magnificent Frigatebird observed in the Cayuga Lake Basin,discovered 21 September 2008 by Cornell students Shawn

Billerman and Tom Johnson. Photo © Tom Johnson

That's huge, so let me repeat that in a slightly different way: Shawn and Tom were watching a Magnificent Frigatebird, not while standing on a beach in Ft. Myers, Florida, but from the middle of the Finger Lakes region in central New York. Within hours (probably minutes) a regiment of birders (sadly, not including me) mobilized and had stellar observations from various points around the south end of the lake. Updates hit the Cayugabirds listserve fast and furious: still circling over Myer's Point, spotted from East Shore Marina, easily observed from Stewart Park.

Magnificent Frigatebird and Ring-billed Gull - one is expected

Magnificent Frigatebird and Ring-billed Gull - one is expectedon Cayuga Lake, the other, not so much. Photo © Tom Johnson

Birders spent the afternoon tracking it as it swirled above Cayuga Lake, tracking it until dusk when it roosted with a gulp of Double-crested Cormorants on a dead tree just west of Stewart Park (did you know a group of cormorants is called a "gulp," according to this USGS page?). Evening posts announced the best locations to watch the bird when it left the roost tree the following morning while some observers, noting the bird's odd posture, such as the drooping primaries and how it held its head between its wrists, speculated about the health of the bird.

Photo © Tom Johnson

Photo © Tom JohnsonSadly, two things were not to be: I wasn't able to make the pre-sunrise trip, which is all for the best as the bird was not in the roost tree when the sun rose. It had expired during the night and was spotted floating in the water. A local birder salvaged the bird, depositing it with the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates where it will be prepared for addition to the specimen collections.

Shawn Billerman photographs the Magnificent Frigatebird

Shawn Billerman photographs the Magnificent Frigatebirdhe co-discovered just days before. The bird will be

prepared for placement in the museum's collection.

During a season when we're all searching for boreal-breeding warblers, sparrows, and the other songbirds that are passing through our area, or focusing on concentrations of raptors streaming by hawk-watching sites, you've got to wonder, "How did a frigatebird make its way from (presumably) the Gulf of Mexico to central New York? And why didn't it survive the night?"

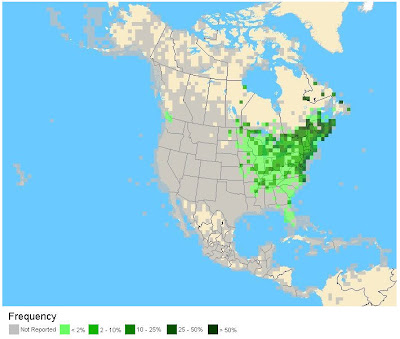

Magnificent Frigatebird observations reported to eBird.

Darker greens show higher frequency of observations,

depicting the expected range. Scattered light green in

the lower-48 are observations of vagrant individuals.

Darker greens show higher frequency of observations,

depicting the expected range. Scattered light green in

the lower-48 are observations of vagrant individuals.

The most obvious answers are hurricane winds and starvation. Hurricane Ike, which made landfall near Galveston, Texas on Friday, September 12, probably carried this bird, along with many other offshore species, onshore. As the storm dissipated the birds made their way towards any large, open body of water. This individual potentially crossed some eight or nine states as it hopscotched across the coastal plain of Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi, the central hardwoods of Tennessee and Kentucky, and followed the Appalachians through West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania before arriving 1,300 miles away from where it started its overland journey on September 21.

After a journey like that a common assumption is that the bird is starving - what does a bird that spends the majority of its time wheeling above tropical waters eat when it finds itself above terra firma? When foraging over the ocean it gorges on small fish, squid, jellyfish, small turtles and crabs, and, before we romanticize this species too much, offal from sewage treatment plants and slaughterhouses.

With a bill like that, would you eat "offal"? Note the

With a bill like that, would you eat "offal"? Note thebright-orange gular pouch, which the males inflate during

breeding, and the purple sheen on the back feathers.

They also parasitize other birds: they chase their target bird until it disgorges their most recent meal, which the frigatebird then catches in mid-air. So, while their familiar foodstuffs may not be found, suitable alternatives should be available -- there are plenty of gulls to be found inland - providing sustenance until they make their way back home to familiar waters.

Though I didn't see the bird in the wild, I did see it in the Lab. Feeling the keel, a quick and dirty method of estimating condition by feeling the breastbone and pectoral muscles, did not indicate an emaciated bird. The keel bone did not protrude beyond the muscle (which would indicate starvation), conversely the bone was palpable, showing it wasn't storing fat. Kim Bostwick, the Curator of Birds and Mammals, mentioned that in addition to preparing the specimen for the collection the stomach contents will be sent to the vet school for analysis. Perhaps those results will shed some light on this bird's fate.

Shawn spreads the toes to show the vestigial webbing

Shawn spreads the toes to show the vestigial webbing(not well seen here, the fault of the photographer).

As unfortunate as it is to see a specimen rather than a live bird, it's also a wonderful moment to study the bird in a way you simply cannot in the wild. Not a better moment, but an equally enlightening experience. Holding this bird, which Tom initially described as a "very unexpected giant black bird," you realize that it is predominantly feathers: it's so light there's barely anything physical to it. Viewing it up close, how else would I get to see the webbing between the toes, a vestigial trait as this bird spends very little, if any, time sitting on the water or swimming? Turning it over to view the back yielded a surprise: the feathers that cover the back are not black, but shimmer with a purple sheen. The head and wings flash metallic green iridescence.

I envy those that watched the bird soaring freely above the Finger Lakes, I feel sorrow the bird wasn't able to follow the contours of eastern ridge of the Appalachians back towards home. But I also feel pride, and satisfaction, that I was able to experience this bird in a way I likely will never see again, especially knowing I won't be able to look at free-flying frigatebirds differently because of this encounter.

I envy those that watched the bird soaring freely above the Finger Lakes, I feel sorrow the bird wasn't able to follow the contours of eastern ridge of the Appalachians back towards home. But I also feel pride, and satisfaction, that I was able to experience this bird in a way I likely will never see again, especially knowing I won't be able to look at free-flying frigatebirds differently because of this encounter.-